Hungarian pianist Etelka Freund died on May 27, 1977 at the age of 98. She was a pianist with a remarkable lineage whose interrupted career and relative dearth of recordings has led to her largely being forgotten; fortunately there has been a relatively recent revival of interest as her scant studio discography and some private recordings have become available.

Born in 1879 (the exact date is not clear), Etelka Freund had a talented older brother Robert who had studied with Ignaz Moscheles, who was a contemporary of Beethoven and friend (and teacher) of Mendelssohn. Robert also studied with Tausig and Liszt, in addition to playing for Brahms. Etelka, some 20 years younger than Robert, had an opportunity to regularly play for Brahms, who admired her very much: when a friend of the composer asked if the young lady played, the composer affirmed in a loud voice, ‘To the enjoyment of everyone!” The composer is also said to have insisted that the Gesellschaft für Musikfreunde have her as a regular member despite her still being a student – she would be their youngest member. Freund also trained with Liszt pupil István Thomán (who also taught Bartók) and Busoni, as well as with her compatriot Bartók, with whom she had a close relationship – and at age 16 she went to Vienna to study with the legendary Theodor Leschetizky.

Although she stopped concertizing between 1910 and 1936 to focus on raising her children, Freund then resumed playing to continued great critical acclaim. She finally emigrated to the US in 1946 and had a successful debut at the Washington National Gallery the following year, but managers were not interested in promoting a 68-year-old pianist.

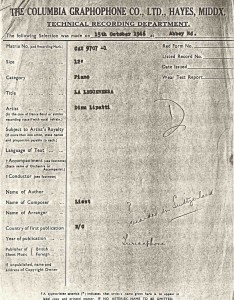

Fortunately, she made a handful of recordings through which her artistry can be experienced, but was largely overlooked despite having maintained her facility to a very old age. It should be noted that a recording of the Chopin Waltzes attributed to Freund is adamantly believed by several leading pianophiles to be a different pianist: Gregor Benko (co-founder of the International Piano Archives) spoke with Freund’s son, who was present at all of her recording sessions, and he had no recollection having set down a single work of Chopin. The same goes for an account of the Schumann Brahms Variations by one Frieda V, long thought to be Freund: it is in fact the Austrian pianist Frieda Valenzi.

Below is a fascinating interview with Allan Evans, who revived interest in her, and the pianist’s son from a radio programme hosted by David Dubal:

Here is perhaps the most important recording in Freund’s discography: a September 1953 recording of the Brahms Piano Sonata in F Minor Op.5, issued on the Remington label (R-199-109). Freund would have been about 74 years old when she set down this account of this titanic Brahms Sonata, a challenging work for an artist of any age. She plays with impressive strength and cohesiveness: melodic lines are beautifully highlighted, chords impeccably balanced, and textures exquisitely clear. Her timing is particularly remarkable, with just the right degree of expansiveness so as to never be exaggerated or sentimental. (Below this account of the Sonata are the two Intermezzi from the same LP.)

Recorded for the same LP was the Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor Op.117 No.2, played a sumptuous sonority, luscious phrasing with elegant singing lines, beautifully balanced textures, and a remarkable rhythmic pulse that maintains momentum without being driven but which is instead incredibly fluid.

Also on that Remington LP was another Brahms Intermezzo, the Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2 – an equally remarkable interpretation, particularly notable for the asynchronization of left and right hands, an effect so wonderfully accomplished that it is not distorted or passé as some might suggestion. And what gorgeous singing tone, poised balance of primary and secondary voices, and incredible timing, with an incredible means of connecting the different ‘chapters’ of the work – a truly mesmerizing performance!

Recorded privately in 1950 and only published on a Pearl CD set that Allan Evans produced is the Brahms Intermezzo in E-Flat Minor Op.118 No.6. The relative constriction of the sound is no impediment to appreciating the incredible depth of Freund’s interpretation. In lyrical passages there is such spacious phrasing that allows lines to breathe as key chords and notes linger, seamlessly blending into what follows, while the stormy middle section is incredibly emotional and powerful.

A previously unpublished radio broadcast of the artist in Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata was included in Marston Records’ superb Landmarks of Recorded Pianism Volume 2 in 2020, a glorious performance that appears to have not been on the radar of a many collectors – you can hear an excerpt of it beginning at 2:31 in the video compilation (featuring a number of pianists) below (note that the image here is of Reah Sadowsky and not of Freund):

One recording of Freund playing Mendelssohn has been made available, a March 8, 1952 recording of the Fantasie in F-Sharp Minor Op.28 – fascinating to hear given her brother’s tutelage with Mendelssohn’s friend and teacher Moscheles. In her 72nd year at the time, she gives a superb performance, with impeccably voiced chords, beautifully shaped phrasing, masterful pedalling, marvellously coordinated articulation, wonderful timing, and gorgeous singing tone.

Freund had a great affinity for the works of Liszt as well, as evidenced by this superb November 8, 1951 traversal of his Funerailles. Linked to the composer’s lineage through her brother and teacher, Freund demonstrates an understanding of his idiom with the amazing atmospheric effects she creates through tone and pedal, along with her transparent voicing. What an incredible resonant rumbling bass, declamatory melodic line, and spacious lyrical phrasing, with incredible power in the towering octaves that belie her age at the time.

As Freund worked directly with Bartók, it is of great interest to hear her way with his music. Just as the composer had once requested that a student playing for him play ‘a little less Bartók-ish’, Freund grasps the concept that his modern harmonic language does not call for aggressive sound: she plays throughout with beautiful tone even as she accents and plays dissonant chords. Wonderfully transparent playing that captures the folkloric nature of the music.

To close, a private 1958 recording of the artist playing with sublime mastery a gorgeous excerpt from Book 1 of the Well-Tempered Clavier: the Prelude in E-Flat Minor and the Fugue in D-Sharp Minor, BWV 853. It could be the influence of Busoni that we hear in her marvellous use of the pedal, accents, and highlighting of motifs as they switch between voices and hands. Even on a somewhat out-of-tune piano, her command is evident through her spacious phrasing, poised transparent voicing, and remarkable use of dynamics to clarify structure and highlight the emotional content. Absolutely beguiling playing by a true master of the keyboard and of music.

Recent Comments